Torre dell'Orologio: medieval clock tower on Piazza San Marco

| Last updated: January 2025 |

Piazza San Marco is at the top of many people's lists when exploring Venice — and it's easy to see why. As soon as you enter the square, the city's most iconic sights surround you. The golden mosaics of the Basilica di San Marco will catch your eye immediately, sparkling in the sunlight. The Campanile di San Marco rises high above, while the majestic Doge's Palace stands nearby, showcasing the city's rich history and power. Around you, lively cafes hum with activity, and their small orchestras fill the air with music. It's a magical place, alive with history and charm.

With so much to see on the piazza, one structure often escapes the attention of many: the Torre dell'Orologio, or the Clock Tower. Despite not being as famous as the other landmarks, the Torre dell'Orologio is definitely worth a closer look.

So, let me share more about the clock tower's history, architecture, and unique features. That way, you'll know exactly what to look for the next time you pass by.

Situated next to the Basilica di San Marco, the Torre dell'Orologio stands out as one of the square's most remarkable structures, making it well worth exploring up close.

|

Torre dell'Orologio |

History of Venice's clock tower

In 1493, Venice's Senate decided the city needed a clock worthy of its status. The aging clock of Sant'Alipio, situated on the corner of the Basilica di San Marco, was no longer reliable or fitting for the world's leading maritime power. Inspired by the magnificent clocks in nearby Padova and Chioggia, the Senate sought to create something even more impressive. They tasked master clockmaker Zuan Carlo Rainieri with designing a precise, state-of-the-art masterpiece to embody the city's ambition and pride.

Rainieri eagerly began crafting the timepiece while the Senate decided on its new location. In 1495, after two years of deliberation, they chose the spot where Venice's most essential elements converged — the intersection of its religious, political, and commercial hub. The Basilica di San Marco and the Doge's Palace stood tall on one side, embodying faith and power. On the other side, the bustling Merceria, lined with shops, connected Piazza San Marco to the Rialto Bridge.

Padova's clock tower, adorned with its astronomical clock, stands proudly in Piazza dei Signori (top left and right). This remarkable timepiece predates Venice's Torre dell'Orologio (bottom). As you can see, the two clocks share some similarities.

The completed Torre dell'Orologio, built between 1496 and 1499, proved to seamlessly connect Venice's religious and political center with its commercial district. From Piazza San Marco, the tower's passageway offered a grand entrance to the Merceria. For those arriving from the Merceria, it beautifully framed the basilica, the Doge's Palace, and the lagoon. Visiting the Torre dell'Orologio early in the morning, before the piazza fills with tourists, lets you enjoy this breathtaking view even today.

Besides the tower's impressive appearance, the clock itself (of course) served a practical purpose. Seafarers departing from the Grand Canal relied on its precise timekeeping to determine the best time to set sail. In fact, the clock's accuracy became so trusted that in 1858, Venice made it the official timekeeper, with every other clock in the city set to match its time.

From Piazza San Marco, the tower offers a monumental entrance to the Merceria (top left). For those arriving from the Merceria, the archway provides a framed view of the basilica, the Doge's Palace, and the lagoon (top right).

Architecture and symbolism

While gazing at the clock tower from Piazza San Marco, do you notice that the facade has several distinctive layers? These layers resemble the hierarchy of late medieval Venetian society.

The base layer, featuring a passageway leading to the shops of the Merceria, represents the least significant aspect of life: earthly goods. Directly above it, Rainieri's clock, adorned with astronomical details, symbolizes the importance of science. However, in medieval Venice, religion held an even higher place. This becomes clear when you look at the statue of the Madonna and Child above the clock.

If you think nothing could outrank religion, think again. The Venetian lion at the tower's uppermost layer serves as a reminder that the government reigned above all. Yet, there's one force no one can escape: time. Crowning the tower are two giant figures striking a bell each hour. A vivid reminder that time rules over all.

Now, let's take a closer look at each layer!

One of the two giant figures, known as 'the Moors,' that stand atop the Torre dell'Orologio.

Southern clock face

Above the tower's archway, the first level features two clock faces. The one on the side of Piazza San Marco is the most iconic. It has a fixed marble outer circle marked with Roman numerals from 1 to 24. The hour hand symbolizes the sun, with a long ray pointing to the current hour.

Looking closer at the clock's dial, you'll spot some differences from modern timepieces. Instead of the usual 1 to 12, this dial features numbers from 1 to 24. Additionally, the placement of the numbers differs. The number 24 sits on the right, where we expect to see 3 o'clock. That's because this clock uses 'ora Italica' (Italian time).

Venice still has many clocks that use the 'ora Italica' system. Some feature a 24-hour clock face, such as the one above the entrance to the Chiesa di San Giacomo di Rialto (top). Others display only six hours, like the remarkable example in the Chamber of the State Advocacies inside the Doge's Palace (bottom left). Meanwhile, the clock face of the Campanile dei Santi Apostoli is split into two 12-hour segments (bottom right).

Unlike today's clocks, which reset at midnight or noon, ora Italica measures time starting from sunset. The hour hand often mimics the path of the sun. At sunset, it points to 24 on the right. Throughout the night, the hand moves along the lower half of the dial. By sunrise, it reaches 12, and at noon, it peaks at 16.

Later, clocks began dividing the day into four six-hour segments, simplifying their mechanics. You can still find these historical clocks on some buildings in Italy.

When Napoleonic troops arrived in Italy in the early 19th century, they introduced the French time system, which started the day at midnight and divided it into two twelve-hour intervals. This system was already in use across the rest of Europe.

Okay, now back to Venice's clock tower. Inside the marble circle, a movable ring displays the Zodiac signs, their related constellations, the names of the months, and the days of the month. At the center, an inner disk shows the Earth. The Moon rotates around it to depict its phases. Especially interesting is how the rings move at different speeds over time, causing the sun and moon symbols to shift through the Zodiac constellations.

The hour hand of the Torre dell'Orologio symbolizes the sun, with a long ray pointing to the current hour. Inside the marble circle, a movable ring displays the Zodiac signs, their related constellations, the names of the months, and the days of the month.

Northern clock face

The second clock face sits on the side of the Merceria. It also features a marble ring with Roman numerals and a sun-shaped hour hand pointing to the hours. Inside the marble ring is a mosaic with golden stars and a copper disk with embossed sunrays, still showing remnants of its original gilding. A once-gilded copper lion of Saint Mark sits at the center.

The clock face on the Merceria side is less detailed than the one facing Piazza San Marco, but its elegant design and the blue mosaic background with golden stars give it a unique beauty.

Statue of the Madonna and Child

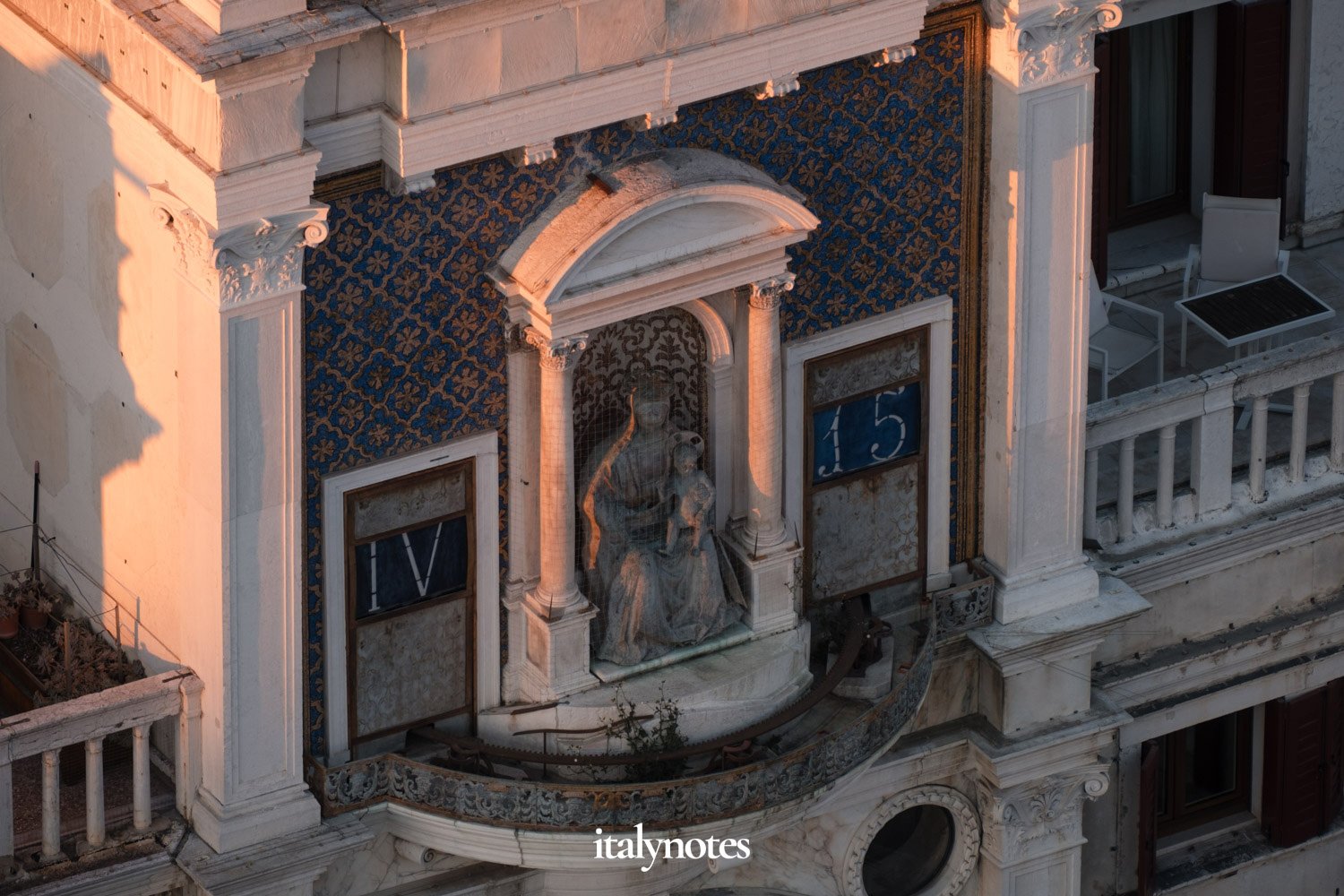

Let's return to the facade on the side of Piazza San Marco. Above the clock, a niche holds a large, gilded statue of the Madonna and Child. Flanking the statue are two blue square displays. The left display shows Roman numerals that indicate the current hour, while the display on the right shows the minutes in Arabic numerals (at a 5-minute interval).

A small balcony extends below the Madonna and Child. It allows wooden figures of the three kings (Magi) and a trumpeting angel to pass before the statue. You can witness this phenomenon twice a year; on Epiphany and Ascension Day, the three kings (Magi) and a trumpeting angel appear twice a year before the statue.

A small balcony stretches beneath the Madonna and Child, allowing wooden figures of the three kings (Magi) and a trumpeting angel to pass before the statue. This event happens twice a year, while the statues are displayed inside the clock tower for the remainder of the year.

Winged Venetian lion

The upper section of the facade features a statue of a winged Venetian lion. If you look closely, you'll notice the statue stands slightly to the left, leaving a small gap on the right. This gap once held a statue of Doge Agostino Barbarigo kneeling before the lion. The French removed the statue after the city surrendered to Napoleon in 1797. They sought to eliminate all symbols of the old regime.

The winged Venetian lion symbolizes both Venice and its patron saint, San Marco. Its paw rests on a book bearing the inscription "Pax tibi Marce, evangelista meus." According to legend, an angel spoke these words to Mark when he sought shelter on a small island in the Venetian lagoon. I discuss this story further in my post about the Venetian lion.

The Moors and the bell

Two giant bronze figures, known as the Moors, stand on the terrace at the top of the tower. Although the statues likely represent shepherds — both wear sheepskins — they earned this nickname due to the dark patina that formed on the bronze over the years.

The figures are hinged at the waist, allowing them to move and strike the bell with their mallet every hour. When you look closely at the Moors, you'll notice one has a beard. People call him 'il vecchio' (the old man), while the other is known as 'il giovane' (the young man). Together, they represent the passage of time. The old man strikes the bell two minutes early, symbolizing the past, and the young man strikes two minutes later, representing the future.

As you can see, the 'Moors' are actually two shepherds draped in sheepskin. On the left stands 'il vecchio' (the old man), and on the right is 'il giovane' (the young man). The old man strikes the bell two minutes before the hour, symbolizing the past, while the young man follows by striking it two minutes later, representing the future.

(Living) inside the tower

Following the inauguration of the Torre dell'Orologio, the Venetian Senate paid Raineri and his family to live in the clock tower and maintain the clock. This marked the beginning of a five-century tradition in which clockkeepers resided inside the tower.

In medieval Europe, the profession of clockkeeper was often well-compensated. The role required basic skills in mathematics and numbers, which were rare at a time when education was not yet widespread.

Today, the Torre dell'Orologio stands empty of its former inhabitants, but you can step into their world by booking a tour. I'll give you a quick look at what to expect.

At the end of the room on the first floor, there are two small windows that look out over the Piazza and the lagoon. The clockkeepers certainly had a room with a remarkable sight! From the first floor, a beautifully crafted metal spiral staircase leads you up to the level that houses the clock's intricate mechanism. It may look complex, but the tour guides are excellent at explaining its key components.

Upon entering the clock tower, a small set of stone steps takes you to a room where you'll learn about the history of the Torre dell'Orologio. The room also offers a clear sight of the fascinating network of pulleys, weights, and counterweights as they silently rise and fall in perfect rhythm.

A metal spiral staircase takes you up to the clock's intricate mechanism, offering a close-up view of the gears that drive both the south and north clocks.

The next staircase takes you to a floor with two rotating frames. These frames, installed in 1858, hold the blue panels — the ones flanking the statue of the Madonna and Child — with the hours in Roman numerals and the minutes in Arabic numerals. Before their installation, two wooden doors stood in their place, through which the statues of the Magi and the Angel with the trumpet appeared twice a year. The statues and the original wooden doors are now stored on this same floor.

Remember the two blue panels flanking the statue of the Madonna and Child on the facade? One displays the hours in Roman numerals, while the other shows the minutes in Arabic numerals. Inside the tower, you can see how this clock operates. The panels are supported by two large rotating frames, and every 5 minutes, the frame displaying the numbers rotates. It's a noisy yet fascinating mechanism to watch.

Climbing higher in the tower leads you to a room that houses parts of the original 15th-century clock mechanism. From here, you can step out onto two side terraces or, via a steep spiral staircase, reach the upper terrace with the two Moors. Not only will you get an incredible close-up of the massive statues, but you'll also be treated to a unique view of Venice and its lagoon.

The view from the side terraces and upper terrace is absolutely beautiful, especially at sunset. In my opinion, it offers the best sight of the Basilica di San Marco. Once that scaffolding is gone, the view will be even more spectacular. If you turn the other way, away from the Piazza, you're in for another stunning sight. On a clear day, the (snow covered) Dolomites rise in the distance, adding to the magic!

Final seconds

Convinced that the Torre dell'Orologio is a true gem? You're not the only one. According to legend, the Senate admired the clock's beauty so much that they feared Raineri might recreate his work elsewhere. And what did they do to prevent this? They gouged out his eyes! A pretty gruesome way to say "thanks," right?!

Luckily for Raineri, this tale remains just a legend. As I mentioned earlier, the Senate rewarded him generously. They even paid him and his family to live in the tower and take care of the clock.

Imagine standing there, between the columns of Saints Mark and Theodore, gazing at the Torre dell'Orologio as your final minutes tick away...

Equally gruesome is the story behind the popular Venetian saying, "Te fasso véder mi, che ora che xe" (I'll show you what time it is). Back in the mid-18th century, executions happened between the two granite columns in Piazzetta San Marco, where the statues of Saints Mark and Theodore stand. The condemned, standing with their backs to the water and facing the Torre dell'Orologio, saw its clock as their final sight. The phrase "I'll show you what time it is" evolved into a threatening reminder of this grim practice.

Similarly, the expression "being between Mark and Theodore" refers to being trapped between two opposing challenges with no escape.

When I first heard the previous story, it made me think of the nearby Bridge of Sighs. The bridge gets its name from the sorrowful sighs of prisoners who, as they were led to their cells, caught one last glimpse of Venice through the bridge's windows. If you visit the Doge's Palace, you can experience this same view.

The last story I want to share isn't directly related to the Torre dell'Orologio, but it happened right next to it. As you walk through the tower's archway toward the Merceria, look up to your left. Above the arch of Sotoportego del Cappello, you'll see a bas-relief of an old woman dropping a mortar. This relief commemorates a pivotal moment in Venetian history when Giustina Rossi, an elderly woman, helped prevent a coup and saved the Republic.

The story goes that on 15 June 1310 (long before the clock tower's construction), Baiamonte Tiepolo, a young nobleman, plotted to overthrow Venice's government. He marched with his troops along the Merceria, heading toward the Doge's Palace. But just before they reached Piazza San Marco, they stopped — an unfortunate choice that would lead to their downfall.

Startled by the noise from the street, Giustina Rossi leaned out of her window. In doing so, she (accidentally?) dropped a heavy mortar, which struck the flag bearer of the rioting army on the head, killing him instantly. The incident threw the rebels into chaos, allowing the regular army to defeat them swiftly.

The bas-relief of Giustina Rossi and her mortar is a silent reminder of the woman who saved the city.

You can find the bas-relief of Giustina Rossi and her mortar above the arch of Sotoportego del Cappello. Tiepolo's house was demolished and a column of infamy was erected bearing the words: "This land belonged to Baiamonte and now for his iniquitous betrayal, this has been placed to frighten others, and to show these words to everyone forever." Nowadays, the column is on display in the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. A humble stone plaque now marks its former location, reading: "Loc. Col. Bai. The. MCCCX.", meaning "Location of column of Baiamonte Tiepolo 1310."

Practical information

|

|